Hawala system (also known as the ‘Hundi’ system in places like Pakistan, حِوالة in Arabic, as ‘xawala’ or ‘xawilaad’ in Somali, and as ‘underground banking’ in the banking sector) originated in South Asia during the 8th century and is used widely throughout the world today, particularly in the Muslim community, as an alternative means of conducting funds transfers. Unlike the conventional method of transferring money across borders through bank wire transfers, money transfer in hawala is arranged through a network of hawaladars, or hawala dealers. Hawala system is a trust-based informal value transfer system (sometimes also referred to as parallel banking) that is used for perfectly legitimate purposes across parts of South Asia, West Africa, and the Middle East, and for facilitating transactions between communities there and people in other parts of the world. Migrant workers in the Middle East and in the West who frequently send remittances to relatives and friends in their countries of origin often use the hawala system for their transactions. Hawala facilitates the flow of money between poor countries where formal banking is too expensive or difficult to access. The commission rates charged by hawala dealers are usually also low compared to the high rates that banks charge. To encourage foreign exchange transfers through hawala, dealers sometimes exempt expatriates from paying the commission fee. But the hawala system also attracts money launderers and terrorist financiers in large part because of the difficulty of tracing the transactions and the limited means of regulatory enforcement. Hawala is generally unlawful in countries like Pakistan and India, and in some parts of the U.S. transactions between hawala brokers are made without promissory notes because the system is heavily based on trust and the balancing of hawala brokers’ books.

You might have heard the term “hawala” in the news or on the internet while reading articles related to terrorism. It was also discussed in Amazon’s new Jack Ryan series and also came upon C-SPAN during the House Financial Services Committee’s Subcommittee on Terrorism and Illicit Finance hearing on Sept 7th on terrorist groups and their means of financing. And if you are a Pakistani or an Indian, chances are you are already very well aware of the Hawala System. It has been a regular part of the discussion in the media in Pakistan and India during ongoing cases of corruption and money laundering in the two countries.

In some ways, Hawala is similar to the Black Market Peso Exchange (BMPE) system: neither tool involves the actual movement of funds—whether cash or wire transfer—across borders. Also, like the BMPE, hawala requires the money launderer or the terrorist financier to place a great deal of trust in the intermediary—the money trader/peso broker in the case of the peso exchange and the hawaladar in the case of hawala.

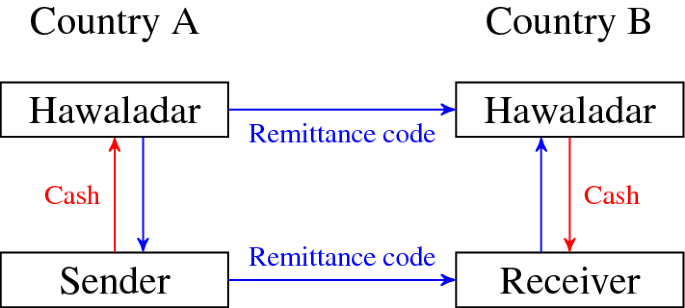

As an example of how it works, consider for a moment that Johnny wants to send $1,000 to Jack in a country with limited banking services. Johnny needs to get the transaction done quickly but also has serious concerns both about the exchange rate as well as the timing and reliability of other services of transfer. Johnny might take his funds to a local hawaladar offering a more favourable exchange rate and faster service—typically a day or two. In exchange for a small commission, the local hawaladar would provide Johnny with a password to send along to his intended beneficiary (perhaps by phone or email), which in this case is Jack. The hawaladar will then give the same password to another hawaladar in the destination country. That hawaladar will have the funds ready to provide to Jack, who is the recipient. No money is moved and no IOUs are signed and exchanged by the two hawaladars since the hawala system is backed only by trust, honour, family connections or regional relationships.

The key thing here is the enormous degree of trust required. The two hawaladars may keep ledgers to ensure that the transactions between them ultimately balance out, or may compensate one another through under- or over-invoicing exported goods, or through other means. The person seeking to send the money entrusts it with the first hawaladar, and also has to trust that the second will deliver an equivalent amount to the intended recipient.

Hawaladars, also called Hawala dealers, keep an informal journal to record all credit and debit transactions on their accounts. Debt between hawala dealers can be settled in cash, property or services. A hawaladar who does not keep his end of the deal is tagged by other hawala dealers as one who has lost his honor and will be ex-communicated from the network or the region.

The Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (“FinCEN”) has a useful guide to hawala and the ways in which it can be used to launder money. Despite considerable uncertainty regarding the extent to which groups funding terrorism actually take advantage of it, the system offers several plus points for those who want speed, anonymity, and extreme difficulty in tracing the transactions.

Here is a useful video from DW English on the Hawala System.