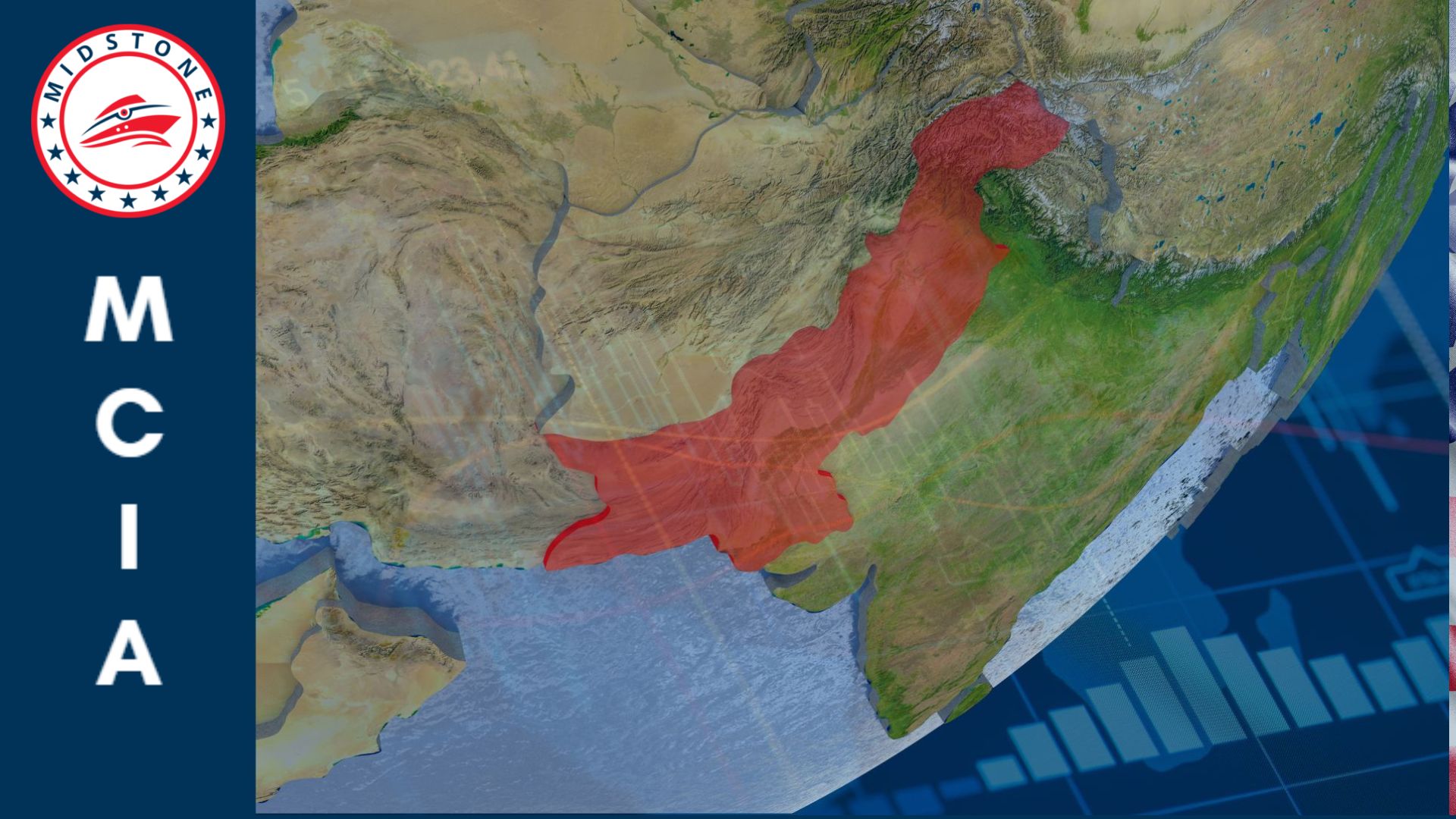

Pakistan faces political and economic turmoil. Not only does the country flirt with bankruptcy, but there are deep political divisions across the whole country. These political differences have seeped into Pakistan’s foreign and national security policies. The unbending policies of the previous Prime Minister Imran Khan put Pakistan in a position which not only exacerbated economic issues created by prior governments, the COVID pandemic and the war in Ukraine but also left Pakistan more isolated and purposeless – this affected Pakistan’s short-term chances of economic recovery, long-term prosperity and the ability to maintain a basic level of necessary security.

The government in Islamabad must take bold, selfless and unpopular decisions both domestically and on the foreign policy front to ensure Pakistan survives this turmoil, otherwise, their government, political parties and possibly the entire country could descend into chaos – this is a responsibility they can’t ignore. But despite economic turnaround being the obvious priority, Pakistan’s new coalition government finds itself struggling to shoulder the huge responsibility of creating necessary immediate economic and political stability.

Sadly, for a Pakistan that produces no critical goods or services, the country faces a real lack of purposefulness to outside powers out of the sphere of national security. Because of this, Pakistan still heavily relies on military diplomacy, which further increases or cements the domestic political influence of the military. When there are fewer avenues for cooperation on mutual national security issues, Islamabad often finds itself struggling to convince outside powers to support it diplomatically or financially, which is particularly problematic as Pakistan relies on international aid, investment and remittances to stay afloat. However, Pakistan’s economic situation is so dire that without immediate international support, such as via the International Monetary Fund (IMF) or loans from traditional lender Riyadh, the country would be be unable to support itself and will likely end up defaulting. This time, Pakistan also finds itself struggling to justify receiving further financial support as it has little to offer in return. Moreover, the IMF is also skeptical of Pakistan’s economic progress due to Islamabad’s economic relationship with Beijing, which includes taking loans at undisclosed high-interest rates from China.

Pakistan has previously taken 22 loans from the IMF, which is more than any other country, and yet it has failed to create domestic economic conditions and policies that favour sustainable economic growth. On Monday, Pakistan’s interior minister Rana Sanaullah said the International Monetary Fund (IMF) hadn’t yet released its $6 billion bailout, despite his government taking difficult decisions such as increasing electricity prices as requested by the IMF, which worsened the public sentiment towards a government accused by some in Pakistan of belonging to a conspiracy to enslave Pakistan to the United States, a conspiracy theory actively led and promoted by former Prime Minister Imran Khan.

On the 13th of July, the IMF reached a staff-level agreement with Pakistan on the policies to complete the combined 7th and 8th reviews of Pakistan’s Extended Fund Facility (EFF), with the ‘immediate priority’ being to stabilize the economy through strict implementation of the budget for the fiscal year 2023 and “adherence to a market-determined exchange rate”.

Traditional allies and lenders Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates declined to support Pakistan with aid packages until the IMF first approves its own funds, while in 2018 they both aided Pakistan without the IMF’s input. This change in approach shows a reluctance to support Pakistan, which stems from a growing political – and to some extent security – disconnect between Islamabad and the Gulf, as well as a reduced purpose for Pakistan in the region, partially as a result of Imran Khan’s foreign policy but also as a result of Pakistan’s obvious inability or reluctance to effectively and appropriately aid the security of their traditional allies and lenders in their confrontation with Pakistan’s hostile neighbour Iran. One notable example is Pakistan’s refusal to deploy troops in aid of the Saudi-led Coalition in Yemen.

While Pakistan’s relationship with traditional Gulf allies is seemingly in a state of decline, rival India’s multifaceted relationship is quickly growing, much to the concern of Islamabad. Given Pakistan’s role in Gulf affairs is seen largely through security, it should concern Islamabad that India has significantly increased security cooperation with both Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. India’s geopolitical influence exponentially grows in the Middle East, as now Israel has sold its Mediterranean Haifa Port to India’s Adani Ports – this is important, as Tel Aviv is viewed as a growingly critical security partner for Gulf countries, and already has excellent defence relations with New Delhi, but Pakistan does not even recognise Israel, meaning Islamabad could be sidelined on security, which is the only thing it can offer something unique towards.

However, there are some positive developments, or rather hints, about an improving Saudi-Pakistan relationship, especially given Saudi Arabia largely views Pakistan’s use through a convergence of purely security interests, such as the need to cooperate more closely on combatting the proxy militant and nuclear threat posed by Iran, something that at least a portion of the Pakistani security establishment seems keen to involve themselves further in, however to a limited degree while trying not to provoke Iran too far beyond Pakistan’s will to escalate.

The stricter conditions imposed by the Gulf come at a time when Pakistan’s army chief has recently received the highest state award from Saudi Arabia. The Prime Minister of Pakistan in a congratulatory message said: “We consider the security of Saudi Arabia as our own and are completely resolved to further cementing our multifaceted bilateral relationship including excellent defence cooperation.” On the 13th, Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman accepted Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif’s invitation to visit Pakistan during a telephonic call.

Resolving Pakistan’s economic woes is and should be the ultimate priority, but Islamabad finds itself juggling difficult domestic decisions as well as an out-of-the-box foreign policy. Without taking unpopular – and therefore difficult – domestic economic decisions, the IMF will not lend Pakistan the money it desperately needs. Without prior IMF support, Riyadh and Abu Dhabi will not support Pakistan economically, which signals a waning relationship between Pakistan and its traditional allies, largely stemming from reduced security cooperation and purpose for Pakistan in the Gulf – without resurrecting better days in their relationship, Pakistan will have even fewer justifications for receiving bailouts from the Gulf.